What does it mean to be useful? IP law once provided protection for “useful” works of invention, innovation, and information. Today, it is useful for preserving the interests of large, powerful rights-holders, often at a cost to creators, consumers, and the economy. IP law should be made “useful” once more.

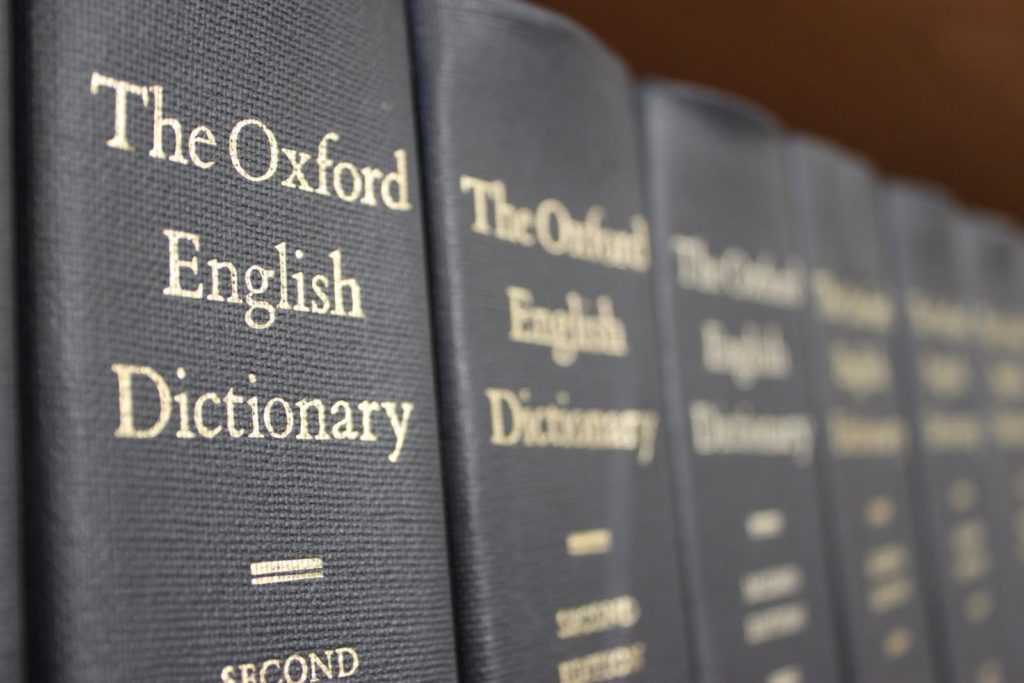

Western copyright finds it’s philosophical roots in two documents, the Statute of Anne and the U.S. Constitution. The Statute of Anne, which was enacted by the British Parliament and predates the Constitution by almost eighty years, provides the protection of copyright “for the encouragement of learned men to compose and write useful books.” The Constitution, no doubt borrowing from the Statute of Anne, secures for authors and inventors the exclusive right to their work, in order “to promote the progress of science and the useful arts.” These documents both explicitly qualify their protection as governing only those works that may be called “useful.” Why?

Western copyright finds it’s philosophical roots in two documents, the Statute of Anne and the U.S. Constitution. The Statute of Anne, which was enacted by the British Parliament and predates the Constitution by almost eighty years, provides the protection of copyright “for the encouragement of learned men to compose and write useful books.” The Constitution, no doubt borrowing from the Statute of Anne, secures for authors and inventors the exclusive right to their work, in order “to promote the progress of science and the useful arts.” These documents both explicitly qualify their protection as governing only those works that may be called “useful.” Why?

Intellectual property law is designed to promote economic progress. If the law can protect the right of innovators to profit from their work, there will be a strong incentive for future innovation. It’s a sound theory, but modern IP law has lost its way. The role of IP law in promoting useful innovation is diminishing.

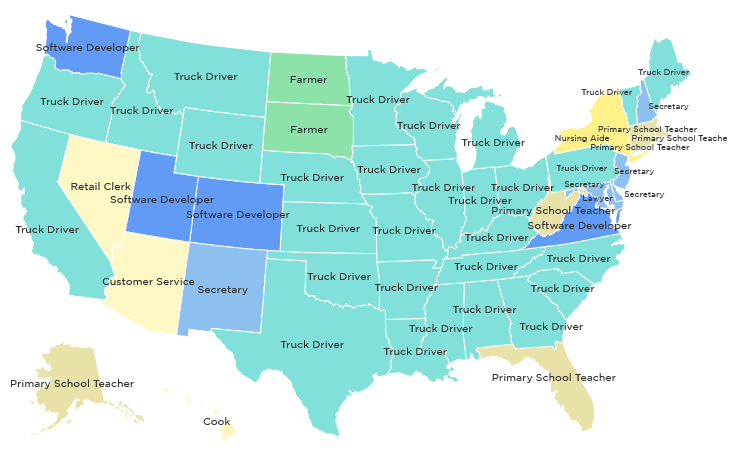

Technically, there is still a usefulness requirement in U.S. IP law. New inventions must be deemed useful to earn a patent. But we ought to be asking, “useful to whom”? Where patents were once used to reward innovators, they are now often used by large companies to restrict competition. Is Apple’s patent of rounded corners on the iPad really useful to consumers or to future innovation? Or is it just protection against future competitors, like Samsung?

The usefulness distinction is even more important in copyright. Copyright incentivizes the creation of information goods in the same way that patents incentivize the creation of physical goods. But there is an important difference between information goods and physical goods that should change how we measure the economic value of copyrights and their usefulness.

Information goods are non-rival. If you know something and explain it to me, my new knowledge doesn’t diminish yours. There are no marginal costs for distributing knowledge from one person to another (or to a thousand others). Therefore, any cost imposed on the distribution of information goods is economically inefficient. Copyrights impose such a cost, as they require payment to access information for which the marginal cost of distribution should be zero.

By pointing out this inefficiency, I don’t mean to argue that copyrights should be discarded. Taxes are economically inefficient as well but there are strong arguments for reasonable taxation, and we as a society have decided that they are necessary. But we have to consider the burden these costs impose on the production of new information goods.

The creation of information goods requires two things: the time and ingenuity of a knowledge producer and the input of other information goods. By creating additional costs for access to information goods, like expensive fees to academic databases, we’ve constrained the production of future information. This counterintuitive effect is one of the negative externalities of copyrights, and it’s all too often overlooked.

The time and ingenuity of knowledge producers needs to be rewarded; they deserve a mechanism to recuperate the opportunity costs of their work. However, the copyright system as it exists today has been coopted by the interests of large, commercial rights-owners. For example, the copyright on works published in the U.S. now runs for seventy years after the death of the author. Copyright for that duration does little to reward the author; any royalties go to the rights-owner instead, which is likely to be a publishing label. Instead, it imposes significant costs on the aggregate production of future information goods.

Again, we should ask ourselves, “useful to whom.” Does a seventy-year copyright “promote the progress of science and the useful arts”? Or does it present an obstacle to further progress?

Intellectual property law must be recalibrated to a standard of usefulness that prioritizes incentives for creativity and innovation. Patents and copyrights should reward innovators and knowledge producers. They should not be used as weapons in ever-escalating corporate feuds. Nor should they be used to extend the ability of corporate rights-holders to profit from the creativity of others. When that happens, when IP law is useful only to the large, well-lobbied few, we all suffer as a result. In a global economy where innovation drives economic growth, getting this question right couldn’t be more important.

If interested, The Wealth of Networks by Yochai Benkler and Remix by Lawrence Lessig are great books that include discussions of the shortcomings of today’s IP systems. Benkler’s work informs my discussion of the economic inefficiencies of copyright and Lessig’s many books on the subject first introduced me to IP law.