There are always people talking at Oxford. You could make it your full time mission to hear all the interesting talks and still miss more than you catch. I thought it would be valuable, both for myself and whomever finds time to read this, to share my impressions from these talks. Views and opinions here will be my own, and don’t necessarily reflect the presenter’s point of view.

The following is my response to a lecture entitled “Personalization, Backpacks Full of Cash, and Rockstar Teachers: The Intersection of Technology, Free-Market Ideology, and Media Hype in U.S. Education Reform.” It was presented at the Oxford Internet Institute by Justin Reich, Phd, Fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society and Founder of EduTechTeacher.

The Educator’s Dilemma: Three questions on technology and education

1) Is education delivered or emergent?

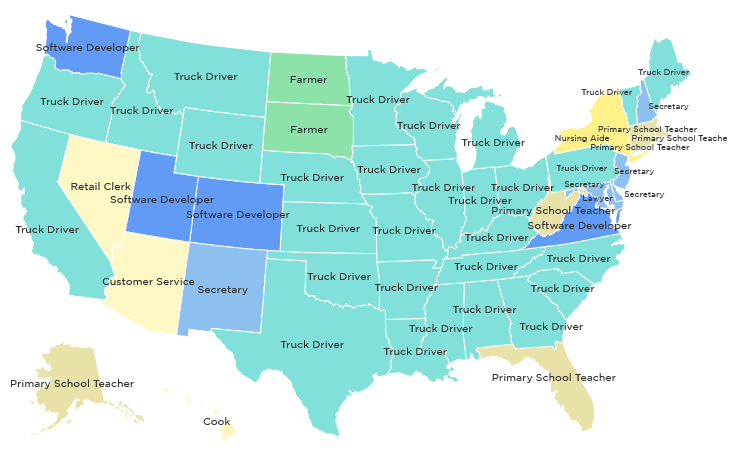

The education system in the United States is broken; there seems to be little argument here. What people do argue about, however, is what to do about it. We’re forced to ask fundamental questions about what education is and what it should be. Should education aim to produced informed citizens? Workers for the labor force? Critical minds? Can it do all three? Should the education system produce anything, or is that a fundamental misconception in itself?

Reich briefly discussed two schools of thought in U.S. education policy, formed around two early education theorists, Edward Thorndike and John Dewey. Thorndike believed in “education as the science of delivery”; Dewey conceived of “education as life” (Reich). Thorndike’s vision won the day, and our education system today largely incorporates his conception of learning. Young minds are empty containers to be filled with facts.

Dewey’s vision for education hasn’t been forgotten though. Reich remarked that educators in the U.S. dream in Dewey and live in Thorndike. As we are forced to reimagine education in the U.S., I think the question deserves another look, particularly as technology offers new ways of educating. Do we believe that education is delivered? That students are to be taught in an industrial, assembly-line manner? Or do we believe that education emerges through experience and discovery? How we collectively answer this question will inform our policy decisions.

2) Where does technology fit in?

There are countless passionate and intelligent people working to fix education; this is the one glimmer of hope for a broken system. These teachers, administrators, policy-makers, activists, are increasingly joined by technologists and investors. Technology is not a silver bullet. iPads do not equal education reform. But I think it’s unequivocally positive that some of the talent and capital of the technology sector are focusing on education. The question is how can technology help? Where does it fit in?

Reich made an important distinction between technology that transforms how we educate and technology that puts a shiny veneer on an old, failing model. He’s right to suggest that improvements at the margin won’t be enough to make an impact. However, another example Reich gives illustrates a problem that technology encounters in entrenched systems like education.

We point to Wikipedia as an example of the marvels of peer production. It is just that, but we forget about the online encyclopedias that failed. Why did Wikipedia succeed where others fail? Reich suggests (based on a forthcoming paper by his colleagues), that Wikipedia succeeded because it developed an innovative process around an established product. Other attempts failed because they made no process improvements or tried to develop an innovative product that was incompatible with users’ entrenched expectations about encyclopedias. When people expect things to work a certain way, it’s hard to disrupt their habits with technology. Education faces a similar barrier, where norms and expectations of how education should be conducted are so deeply ingrained, particularly in parents. This could prove an obstacle for real technology-driven innovation in education.

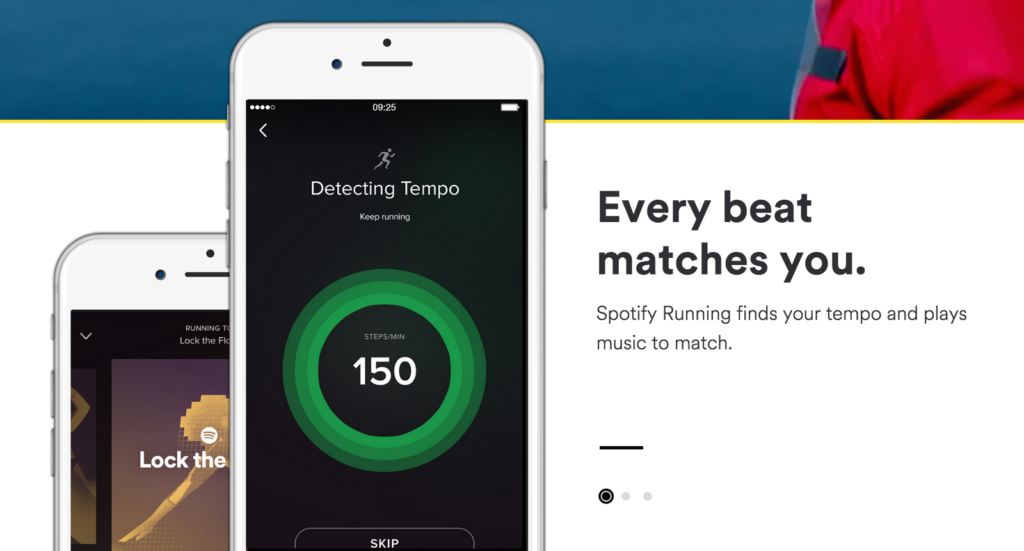

One answer may exist in systems like Khan Academy, which preserves traditional teaching practices (like lectures and tests) but reimagines delivery methods (by enabling personalization of lessons). Here again we encounter the delivery vs emergence debate, but as I’ll discuss later, I think there’s a middle ground.

3) How do we test and implement new technologies for education?

Product development requires an iterative process of release, review, and improvement. Startups are told to build a “minimum viable product,” get it in the hands of real users, see what works and what doesn’t, and rebuild or pivot as necessary. This model can be effective for building quality products quickly , and education would benefit from adopting it. However, any iterative process anticipates and accepts failure. While this failure may be celebrated in the context of product development, it becomes a problem in education.

When six online encyclopedias fail and one succeeds, we say the market functioned as it should. We value Wikipedia and are generally no worse for the failure of the others. In education, those failures affect the development of children. Failure, a necessary component of developing a quality product, can’t be accepted and celebrated in the same way. The response may be that the system fails certain children so badly and predictably, as indicated by zip code, race, socioeconomic status, etc, that we might as well try something else. It seems unethical, though, to experiment with new practices on an already underserved population just because the status quo is so inadequate.

Where do we go from here?

First, passionate and intelligent people need to keep trying. Technology won’t solve anything on it’s own, but introducing new people and ideas to the education debate can’t hurt. In that spirit, I’d like to make a suggestion.

Let’s start with a perspective that views technology as a supplement, not a replacement to classroom interaction and teacher engagement. For core curricula, particularly in math and science, a system like the Khan Academy can deliver lectures and assessments. Teachers, therefore, are free to work more intensively with students that need it, either for remediation or advanced work.

The model then becomes a hybrid of the delivery and emergence philosophies. Students receive instruction in a standardized form but are able to progress through the material at their own pace. As we learn more about how students use the system, we can develop mechanisms for allowing them to chose topics that they find most engaging. They learn by exploration as well as delivery.

For implementation, we direct a fraction of education budgets to funding small pilot programs. The programs should be small and targeted particularly to those most in need of improved education programs. However, the programs should be an option, something parents and children could opt-in to. Funding should be available to ensure that economic factors don’t impede children from enrolling. That would likely mean transportation assistance and potentially after school programs, as the pilot programs may be located at a greater distance from home than local schools. By making the programs voluntary and free, we might mitigate as much as possible the complex ethical questions discussed earlier.

These are meant as humble suggestions. I suspect that programs like this probably exist already, in some form or another, and that things are always more complicated than they appear from the outside. But the more fresh perspectives we can bring to the education discussion, the better off I think we’ll all be.

I’d also like to point out a serious gap in using technology to educate in the humanities and arts. Despite the dire need for scientists and engineers, to forsake english, history, theology, philosophy, music and all the wonders of the humanities would be a travesty. We need people who can think, who can act as citizens of the world and approach questions of science and nature from an informed and ethical position. These things cannot be achieved in math and science alone.

The most hopeful thing that Reich presented was a single number: 15,000. There are about 15,000 school districts in the United States. If we can supply these districts with the framework, technology, and funding to innovate as they see fit, we can make this work. We have to.